The Potential Pitfalls of a Bayer-Monsanto Merger

Alarm bells have been ringing since agribusiness giants Bayer and Monsanto announced their proposed merger in September 2016.

The deal is the latest in a series of multibillion-dollar agriculture mergers that, if approved, would give a few multinational corporations unprecedented control over the chemicals and seeds on which farmers rely. While Bayer and Monsanto say the merger will lower prices, allow for greater innovation, and boost crop yields, many in the industry expect the exact opposite to occur. There are also concerns about the effects of the megamerger on consumers and the environment.

Bayer and Monsanto have long histories of pursuing profits at the expense of people and the planet.

Separately, Bayer and Monsanto have demonstrated a willingness to single-mindedly pursue profits, sometimes at the expense of people and the planet. Together they have the potential to do even more harm, yet their consolidated power could allow them to escape consequences through regulatory capture.

At the heart of the Bayer-Monsanto merger controversy is a simple question: Who benefits from large corporations having enormous influence over our food supply?

ClassAction.com takes a look at the possible impacts of a Bayer-Monsanto merger and reminds you that we help people fight back against corporate power. In fact, we have filed a lawsuit against Monsanto and other companies for allegedly damaging farmers’ crops with herbicides.

Bayer and Monsanto: “A Marriage Made in Hell”

To better understand the future marriage between Bayer and Monsanto—which Friends of the Earth Europe has called "a marriage made in hell"—one must examine these companies’ pasts. Each of their histories contain dark episodes that should give pause to anyone concerned about the environment and public health.

For starters, it’s worth asking how Bayer—a German pharmaceutical company best known for products like Aspirin and Alka-Seltzer—and St. Louis-based Monsanto, a former chemical company, got into the agriculture business.

A Brief History of Bayer

Bayer was founded in the 1860s. Its first major products were the pain reliever Aspirin and (believe it or not) heroin, the latter of which was marketed as a cough suppressant and non-addictive morphine substitute. “Heroin” was a Bayer trademark for decades.

During World War I, Bayer was involved in the development of chemical weapons such as chlorine gas. After the war ended, German chemical giant IG Farber took over Bayer. Dozens of IG Farben board members and executives were sentenced to prison at the Nuremberg Trials for alleged war crimes of the Nazi regime, including mass murder and slave labor.

The Allies broke up IG Farben following World War II and Bayer was reestablished as an independent business. An IG Farben board member sentenced at Nuremberg was elected the head of Bayer’s supervisory board in 1956.

Bayer’s postwar period products have included the neuroleptic Chlorpromazine, Primodos—a controversial pregnancy test pulled from the market in the mid-1970s for alleged birth defects—and the clotting agent Factor VIII. Recent reports suggest that in the 1980s, Bayer knowingly sold HIV-contaminated Factor VIII to Asia and Latin America after the agent was pulled from U.S. and European markets. Bayer’s statin drug Baycol, introduced in the 1990s, was linked to more than 50 deaths.

As the website Corporate Watch details, Bayer has also drawn scrutiny for its monopoly on the anti-anthrax drug Cipro, suing South Africa to protect profits from its patented AIDS medication, funding health and environmental groups that affect public policy pertaining to many of Bayer’s products (including pesticides), the heavy use of antibiotics in livestock that has led to antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and the production of toxic pesticides and insecticides. Neonicotinoids (neonics), a type of pesticide produced by Bayer, has been linked to the collapse of bee populations.

The proposed deal would give Bayer control over one-quarter of the world's seed and pesticide supply.

Bayer is one of the companies that has profited from the so-called “Green Revolution” that replaced traditional agriculture with high-yield patented seeds and agrochemicals. During the 1990s the company sold millions of dollars of agrochemicals to developing countries with the help of loans secured through the World Bank.

Bayer became a market leader in GMOs and agribusiness when it acquired Aventis CropScience and merged it into their CropScience agrochemical division in 2002. That same year, Bayer acquired one of the top five seed companies in the world (at the time), the Netherlands-based Nunhems.

Bayer offered $66 billion last year to acquire Monsanto. If approved by regulators, the deal would make Bayer the world’s largest seed and agriculture chemicals company, with control over roughly one-quarter of the world’s seed and pesticide supply.

A Brief History of Monsanto

Founded in 1901, Monsanto’s first major product was the artificial sweetener saccharin, which has been linked to cancer in mice and rats.

During the 1920s Monsanto moved into chemical production, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), a known human carcinogen that the United States banned in 1979. Monsanto claimed that it was not aware of PCB toxicity until the late 1960s, but internal company memos show that the company knew about the dangers early on and engaged in an extensive disinformation campaign.

The company that helped bring us nuclear weapons, PCBs, and dioxins shifted its focus in the 1970s to agricultural chemicals.

In the 1940s, Monsanto played a role in the Manhattan Project (which produced the first atomic weapon), became one of the first manufacturers of the insecticide DDT (banned in the 1970s for its toxicity), and began promoting the use of agricultural pesticides containing dioxins (one of the so-called “dirty dozen” environmental pollutants).

In the 1960s Monsanto used dioxin to manufacture the defoliant Agent Orange. Agent Orange was sprayed extensively by U.S. forces in the Vietnam War to clear jungle and is estimated to have contaminated millions of Americans and Vietnamese, resulting in countless deaths, disabilities, and birth defects. As with PCBs, Monsanto used questionable science to present dioxin as safe, but internal company documents later showed that Monsanto had long known about dioxin’s deadly effects.

The company that helped bring us nuclear weapons, PCBs, and dioxins shifted its focus in the 1970s to agricultural chemicals, with a focus on herbicides—in particular the herbicide glyphosate (Roundup).

Marketed to farmers and consumers as environmentally friendly, evidence is emerging that Roundup—the most-used agricultural chemical of all time—is a human carcinogen. There is also evidence that Monsanto colluded with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to conceal Roundup’s risks.

The World Health Organization has named glyphosate a probable human carcinogen, and California recently added glyphosate to a list of potentially cancerous chemicals and may add warning labels to products containing the chemical.

Use of Roundup increased dramatically when Monsanto introduced genetically modified “Roundup Ready” crops. These crops contain a gene that allows them to survive glyphosate as it kills surrounding weeds.

Despite widespread public skepticism about GMO safety, the scientific consensus is that GMOs do not pose a threat. The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicines released a report in May 2017 declaring GMOs safe for both humans and the environment. But critics point out that the National Research Council—the research arm of the National Academy of Sciences—has financial ties to Monsanto, the world’s biggest seller of GM crops, and other GMO-friendly businesses.

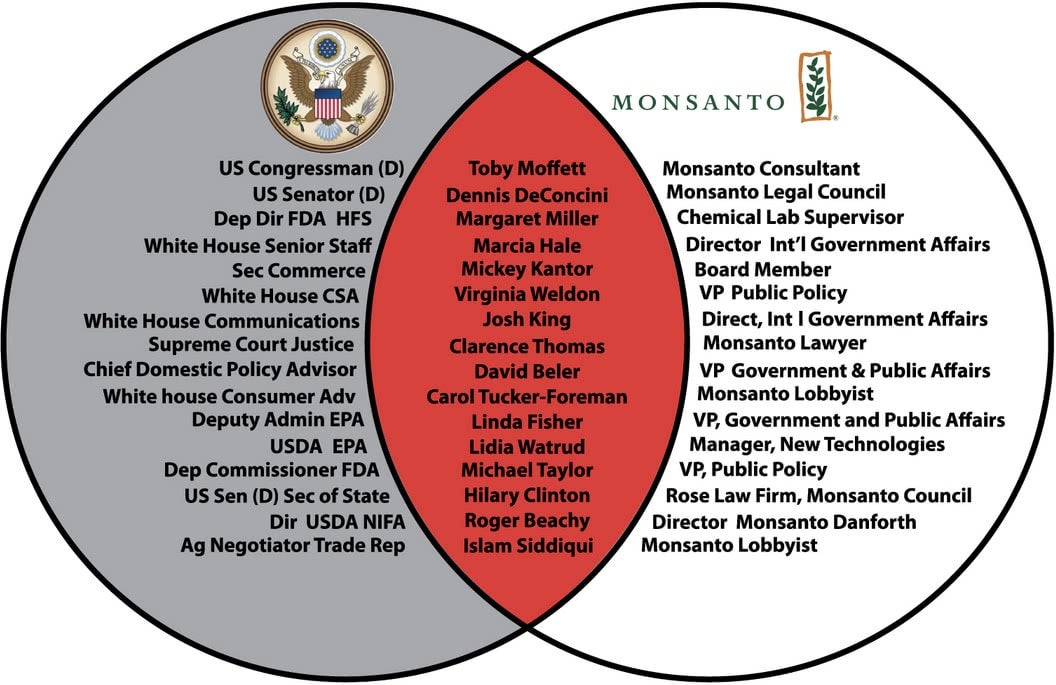

Image Source: Occupy Sonoma County

Who Benefits from the Merger?

When top executives at Bayer and Monsanto are asked to defend the companies’ merger, they argue that consolidation is necessary to drive agricultural innovation, increase crop yields, and reduce farming input costs.

Shortly after Bayer’s bid to acquire Monsanto was announced, Bayer CEO Werner Baumann and Monsanto CEO Hugh Grant were interviewed by CNBC. Mr. Baumann said of the deal, “We can bring better solutions, faster to the growers so they can help contribute to feeding an ever growing world. That’s what this is all about.”

Mr. Grant echoed these sentiments, telling CNBC that the Monsanto-Bayer combination would “unlock future innovation growers desperately need at the moment.” He pointed to a ten-year low for corn prices and a five-year low for wheat prices.

"The mergers are as much about maintaining profit and staying financially healthy as they are about the development of new technologies."

In a separate statement, Monsanto chief technology officer Robb Fraley said, “The whole agricultural industry is basically going through a transformation. It’s the last big industry in the world to be digitized.”

The merger, says Fraley, “allows us to make more investments, have more capabilities and build better products for farmers, that they can use to grow crops with higher yields… and farm better, farm smarter.”

While it is true that the agriculture industry is in the midst of a recession—American farm revenue dropped from $120 billion in 2013 to $62 billion this year, and the costs of seeds, pesticides, and fertilizers have risen by double digits over the last 4-5 years—it is also true that Monsanto and other agricultural giants are going through a sales slump. Monsanto said in 2015 that it would lay off 12 percent of its employees.

“From that perspective,” writes Quartz, “the mergers are as much about maintaining profit and staying financially healthy as they are about the development of new technologies.”

(Click below for page 2.)

In light of the downturn, some farmers are willing to take a risk on agriculture companies getting bigger if it means reduced input prices. Others, however, fear that consolidation will lead to further rises in the costs of seeds and chemicals due to the blocking out of smaller competitors.

Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa, the nation’s largest corn producer, was blunt in his assessment of a Bayer-Monsanto merger. “When you have less competition, prices go up,” said Mr. Grassley.

"When you have less competition, prices go up."

Less competition could mean not only higher prices, but also less diversity in seed and chemical choices. “Large companies’ model of innovation has served as a barrier to entry for smaller companies interested in developing more choices for farmers,” said Matthew Crips of agricultural technology firm Benson Hill Biosystems.

Tightening the Reins on Farmers

Big Ag controlling farmers by selling them patented GMO seeds that cannot be saved and replanted the next year is a common talking point among GMO opponents. But that line of thinking misunderstands plant genetics.

Many farmers choose not to save seeds because doing so is likely to produce reduced yields and increased susceptibility to disease. And farmers say they do have choices when it comes to the seeds they plant. Those that choose GMO seeds simply feel that it is the best choice based on a range of factors.

Big Ag megamergers could restrict the range of seeds and pesticides to which farmers have access, especially small and organic farmers, which would be increasingly vulnerable in a system that favors large-scale, intensive monoculture production using chemical inputs.

A move to this kind of system could be Big Ag’s master plan. Environmental group Friends of the Earth Europe explains how Bayer, Monsanto, and other agriculture giants are working with tech companies to develop data platforms that will allow them to collect and analyze data on soil, weather, and plant health and to use this to advise and supply farmers.

“This gives the companies enormous power over farmers, who are likely to find themselves tied into whole chains of products, limiting their freedom to choose the inputs and methods they use,” Friends of the Earth explains.

If the goal of Roundup Ready crops (glyphosate-resistant seeds) was to sell more Roundup, then it is reasonable to assume that the “datafication” of agriculture is a way to sell more of the agriculture products and services offered by a combined Bayer-Monsanto.

Monsanto has described data science as the “glue” that connects its breeding, biotechnology, chemistry, and microbes offerings. It could also be the glue that forces farmers to stick with the company in a feedback loop of corporate profits.

"Fewer and fewer options are available to farmers at a time when consumers are demanding more and more choice."

“Big Ag wants to tie farmers into a system where they have further control of our food and the data linked to it," Tiffany Finck-Haynes of Friends of the Earth told ClassAction.com. "Agrochemical companies, including the farm machinery and fertilizer companies, are all consolidating, resulting in a corporately controlled and concentrated digital agriculture platform that locks farmers in.

"Fewer and fewer options are available to farmers at a time when consumers are demanding more and more choice. Our food system is broken, and any further consolidation of agriculture companies will only break it further."

Trickle-Down Effects of Consolidation

Whatever the results of Big Ag consolidation are on food production, consumers will feel the effects. Rising seed and input prices would push up food prices; reduced choices for farmers would mean fewer varieties on shelves; a further industrialized food system could threaten organic food supplies; and more chemicals on crops means more chemicals in our diets and in the environment.

American consumers have made their voices heard; we are eating more organic food than ever and the “locavore” movement of buying local, sustainable food is sweeping the nation. From 1994 to 2013, the number of farmers’ markets rose more than 350 percent. The top reasons cited for buying organic foods include supporting local farmers and avoiding exposure to toxins.

But in a parallel reality, Big Ag wants to take us in the opposite direction. Which again begs the question: who benefits from the corporatization and industrialization of our food supply?

Promises vs. Results: Examining the Industrial Farming Track Record

The promises of Big Ag to help farmers and increase yields are nothing new. From the start, Monsanto has touted the enormous potential of genetically modified crops and industrial farming techniques. They are now doubling down on promises to offer better farming solutions for the benefit of all.

The solution to Monsanto-caused problems appears to be more Monsanto “solutions.”

But it’s hard not to be cynical about these claims. Over the last 15 years, Monsanto has grown more than sixfold to a value of over $100 billion. Sales of Roundup and Roundup Ready crops have largely driven this growth.

Over the same period, U.S. crop yields have also grown—but compared to yields in Europe, which has rejected GM crops, the results are underwhelming. European farmers, meanwhile, have reduced their use of pesticides, while their American counterparts are using more chemicals. U.S. seed prices have also risen dramatically.

A report from the National Academy of Sciences concluded that there is “little evidence that the introduction of GE crops were resulting in a more rapid yearly increases in on-farm crop yields in the United States than had been seen prior to the use of GE crops.”

An analysis by the New York Times that compared crop yields in the U.S. and Canada to those in Western Europe found “no discernible advantage in yields” for farmers in North America. In addition, France—Europe’s largest producer, one that does not allow GMOs—has seen herbicide use decrease by 36 percent, while in the U.S. herbicide use has increased by 21 percent.

Monsanto’s Roundup Ready crops were theoretically supposed to decrease herbicide usage because farmers can replace a cocktail of herbicides with glyphosate and avoid tilling farmland to kill weeds, thus reducing runoff. But an unintended consequence has been glyphosate-resistant “superweeds” that necessitate higher doses of glyphosate and other herbicides.

Conveniently, Monsanto has solutions to the superweed problem at the ready, including new herbicides and new generations of Roundup Ready crops.

GMO crop patents generally last about 20 years, and once they expire, companies can produce off-patent generic GMOs. The Roundup Ready patent expired in 2015. Roundup Ready 2 was introduced in 2009, and a third generation is in the works.

Monsanto has also introduced crops resistant to the herbicide dicamba. Some of these dicamba products have allegedly volatilized, become airborne, and moved onto other farmers’ properties, causing huge yield losses for their non-dicamba resistant crops.

In short, the solution to Monsanto-caused problems appears to be more Monsanto “solutions.” This, no doubt, is a great business model. But it is hardly a model of security for farmers, those that depend on them, or the environment.

Bayer and Monsanto want us to believe that their joining together is for the greater good. Yet in the final analysis, the companies’ track records give the public few good reasons to support a merger—and many good reasons to fear it.