Victims Look for Answers as Opioid Epidemic Sweeps America

A drug overdose epidemic is sweeping America, led by a dramatic surge in deaths from opioids—a powerful, highly-addictive class of drugs that includes natural and synthetic analgesics such as morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone, and fentanyl, as well as heroin.

Those responsible for America’s opioid epidemic have largely escaped legal consequences, but people from the hardest-hit states are starting to fight back.

Heroin is the product of an underground drug trade pushed in back alley deals. Prescription opioids are shipped from warehouses, prescribed in doctor’s offices, and picked up at pharmacies.

One drug cartel operates on the black market, the other in white lab coats. But their products are nearly identical, both in their chemical composition and their ability to destroy lives.

Indeed, a patient who begins a painkiller regimen at a clinic very often ends up buying drugs on the street. And all too often, that same patient ends up dead.

Protected by powerful interests, those responsible for America’s opioid epidemic have largely escaped legal consequences. People from the hardest-hit states, however, are beginning to fight back.

Prescribing Trends Drive Overdoses

Last year the U.S. death rate increased for the first time in a decade, and overall life expectancy dropped for the first time since 1993.

Since 1999, the number of prescription opioids sold has almost quadrupled.

These sobering statistics coincide with 33,091 deaths from illegal and legal opioids in 2015—an increase of more than 200% since 2000—including more than 15,000 from overdoses involving prescription opioids.

More than six out of ten overdose deaths involve an opioid. Every day, 91 Americans die from an opioid overdose. Nearly half of all opioid deaths involve a prescription opioid.

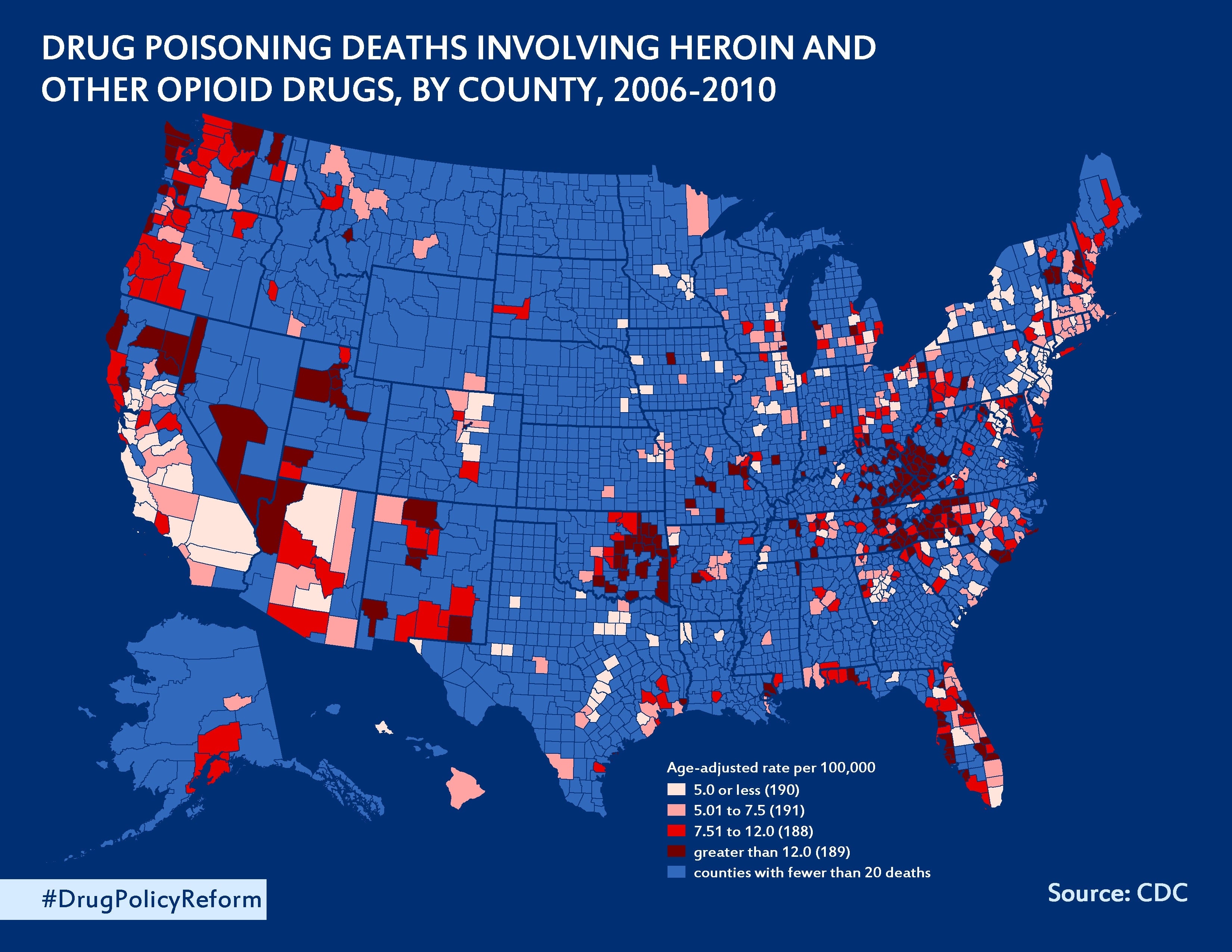

Heroin overdose deaths, which have more than tripled in the past four years, are closely correlated with prescription opioids. The CDC reports that past prescription opioids misuse is the strongest risk factor for heroin use. Four out of five heroin addicts were initially addicted to prescription opioids.

Since 1999, the amount of prescription opioids sold has almost quadrupled. Over the same period, prescription opioid deaths have more than quadrupled.

But the amount of pain Americans report has not changed. There is also a lack of evidence to support opioids’ long-term effectiveness for managing chronic pain.

In fact, a 2016 University of Colorado study found that opioids actually increase chronic pain.

This could help explain why prescription opioid users frequently require higher medication doses to achieve the same pain relief. Higher opioid doses make it more likely that a patient will become addicted.

As the dose increases, so does the overdose risk. Overdosing on opioids can stop a person’s breathing, causing permanent brain damage or death.

Drug Companies Capitalize on Expanded Indications

Before the 1980s, prescription opioids were primarily prescribed for short-term pain and chronic pain associated with cancer and the end of life.

The medical community’s fundamental rethinking of pain in the mid-80s—from a symptom that should be tolerated to a vital sign that doctors could measure and treat—paved the way for prescription narcotics’ emergence.

Drug companies, seizing on expanded pain pill uses, began introducing new drugs and aggressively marketing them.

One company in particular, Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin, exemplified the industry’s focus on chronic non-cancer pain.

OxyContin was approved in 1995. From 1996 to 2002, OxyContin sales increased from 300,000 prescriptions ($44 million) to 7.2 million prescriptions ($1.5 billion). Over this period the number of Purdue sales representatives more than doubled.

In 2001 alone, Purdue spent $200 million on OxyContin marketing. Sales representatives received six-figure bonuses.

In 2001 alone, Purdue spent $200 million on OxyContin marketing.

High-prescribing doctors were compiled in a company database and targeted. Branded promotional materials—including hats, plush toys, coffee mugs, and coupons for free OxyContin prescriptions—were distributed to practitioners.

Purdue also conducted “pain conferences” where physicians gave paid speeches and targeted doctors with medical journal advertisements.

But the marketing frenzy was based on a fundamental lie. Purdue claimed that OxyContin’s patented time-release formula posed an addiction risk of less than 1 percent. Sales reps told some doctors that the drug didn’t even cause a buzz. Meanwhile, Purdue rolled out stronger pills with even higher addiction and abuse risks.

In this way, a supposedly non-addictive, heroin-like drug was prescribed to millions of patients who in years past would have been given an over-the-counter drug.

Distributors, Doctors, and Pharmacies Get in on the Game

Drug companies like Purdue Pharma bear outsize blame for America’s opioid epidemic, but they’re not the only ones responsible for flooding communities with narcotic pain pills.

West Virginia—one of the states hit hardest by the epidemic—shows a multi-pronged conspiracy.

Over six years, according to the Charleston Gazette-Mail, 1,728 West Virginians suffered fatal opioid overdoses as drug wholesalers poured 780 million hydrocodone and oxycodone pills into the state—an amount equal to 433 pain pills per resident.

Just three wholesalers supplied more than half of the pills. The companies have total revenues exceeding $400 billion. Their top executives pulled in more than $450 in compensation over the past four years as the West Virginia opioid death toll climbed.

The middlemen, however, had help from pharmacies and doctors.

For example, the Gazette-Mail reports that some small, independent drugstores and pharmacies ordered 1.1 million to 4.7 million opioid pills per year.

A report in The Guardian describes one “pill mill” pharmacy in Williamson, West Virginia that filled up to 200 opioid prescriptions per day.

Some doctors and clinics are willing pill mill accomplices.

Opioid-addicted patients, many of whom get hooked after an initial prescription for pain, “doctor shop” among numerous providers. Some doctors and clinics, however, are willing pill mill accomplices.

One Williamson clinic with a reputation for no-questions-asked prescriptions made $4.5 million per year. The doctors—including a Pennsylvania physician who sent blank, pre-signed prescriptions to the clinic—often did not even see the patients for whom they were prescribing pills.

Lawsuits Seek Accountability

In 2006, as the opioid epidemic gained attention, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) began cracking down on the drug distribution chain.

A groundbreaking West Virginia lawsuit seeks damages from doctors, pharmacies, and distributors that formed a “veritable rogue’s gallery of pill-pushing.”

Civil cases against manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies, and doctors reached 131 in 2011 but dropped to 40 in 2014, reports The Washington Post.

The reason for the decline was industry pushback. Drug companies hired former DEA and Justice Department officials to lobby against industry prosecution. Soon after, DEA officials began delaying and blocking enforcement actions.

At the state level as well, drug-makers have blocked measures aimed at curbing prescription opioid distribution. Using lobbyists and campaign contributions, drug companies have outspent anti-opioid activists by more than 200 times, according to the Associated Press.

The state of New Hampshire, which had the third highest rate of drug overdose deaths in 2014, has filed subpoenas against drug companies seeking information about how prescription painkiller are marketed in the state. The state has three attorneys on the case. The pharmaceutical companies have 19. So far, the investigation hasn’t produced a single document.

But not all legal efforts against the prescription opioid racket have fallen flat.

In 2007, Purdue Pharma pleaded guilty to misleading doctors and patients about the addictive potential of OxyContin and misbranding the drug as “abuse resistant.” And in 2015, after a nine-year legal battle, Purdue agreed to a $24 million settlement with the state of Kentucky for alleged Medicaid fraud involving OxyContin.

A groundbreaking West Virginia lawsuit filed by 29 plaintiffs who survived opioid addiction or lost a loved one to painkiller addiction seeks damages from doctors, pharmacies, and distributors that formed a “veritable rogue’s gallery of pill-pushing.”

West Virginia’s highest court rejected claims by the defense that admitted drug abusers should not be able to sue, citing the legal principle of comparative fault.

“What is it going to take before we as a nation accept that we are the victims for the most part and the doctor, the pharmacist and pharmacies are the perpetrators feeding off the lives of others?” said plaintiff and former opioid addict Wilbert Hatcher.

America’s opioid epidemic is an unprecedented public health crisis. Holding the responsible parties accountable may just require unprecedented litigation.