Self-Driving Car Companies Lobby Congress, Win Big

A gridlocked Congress that can agree on almost nothing has found common cause on the issue of self-driving cars.

On October 4 the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee approved a bill that would get self-driving cars to market faster by loosening regulatory controls. The bill is similar to one the House of Representatives passed in September, allowing hundreds of thousands of autonomous vehicles per year on public roads. Both bills give the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) sole authority to regulate autonomous vehicle design and performance.

Safety groups and the driving public remain skeptical about whether driverless vehicles are ready for wide deployment.

Proponents say the sweeping legislation is needed to address a patchwork of state and federal laws. They hail driverless technology as a transportation panacea that will save lives, create jobs, cut down on gridlock and pollution, and reshape communities.

But safety groups and the public remain skeptical about whether driverless vehicles are ready for wide deployment. And lurking in the background are powerful corporate interests with a huge stake in rapid adoption of the technology—regardless of the risks.

House and Senate Bills Agree on Major Points

While the legislation is a work in progress—the Senate bill still requires a full vote, and then the House and Senate versions would have to be reconciled before being sent to President Trump—both bills aim to put self-driving cars on the road faster through several major changes to existing laws.

NHTSA at the Wheel

The House and Senate bills grant the NHTSA authority on autonomous vehicle design and performance standards. States retain authority over licensing, insurance, and public safety laws. States can allow or prohibit self-driving cars on their roads, but they must defer to the NHTSA on vehicle regulations.

This arrangement is similar to how state and federal governments regulate traditional cars. Local officials, however, have expressed concerns over their ability to protect residents from the largely unproven technology. They claim their authority is meaningless if no one is technically driving a car.

Reduced Barriers to Deployment

Under the new legislation, automakers could obtain more exemptions from federal motor safety standards that apply to all new vehicles.

Current standards reflect human drivers and require features like steering wheels and brake pedals, which aren’t relevant for driverless cars. As of now the NHTSA permits an annual exemption to cover 2,500 vehicles per manufacturer. That number would increase under the House bill, allowing up to 25,000 autonomous vehicles per manufacturer in year one; 50,000 in year two; and 100,000 in years three and four. The Senate bill tops out at 80,000 exemptions after three years and lifts the cap completely after four.

Exempted vehicles must be shown to be at least as safe as human-driven cars. A manufacturer granted an exemption is required to provide information about all crashes involving exempted vehicles. The House bill gives the NHTSA two years to issue a final rule regarding how safety is being addressed by each manufacturer.

Cybersecurity and Privacy

Automated driving systems present serious cybersecurity risks, including the disclosure of passenger data and the ability of hackers to remotely control a vehicle. Thankfully the House and Senate bills recognize these risks and call for manufacturers to develop cybersecurity and privacy plans.

Manufacturers are required to develop and execute a comprehensive plan for identifying and reducing vulnerabilities and responding to unauthorized intrusions. Likewise, manufacturers must have a privacy plan in place describing how they’ll collect, use, share, and store passenger data. They must also describe how customers are notified about the privacy policy and what choices they have regarding their data.

Commercial Vehicles Exempted, but Roll On

Vehicles over 10,000 pounds were not included in either bill, reflecting labor union concerns about commercial driver job losses.

Many in the industry, however, see a silver lining. Chris Spear, president of the American Trucking Associations, likened truck drivers to pilots last year in a statement to Congress, noting that drivers will still be needed to do the pickups and deliveries in cities, much the way that pilots control taxiing, takeoff, and landing, but revert to autopilot at cruising altitudes.

Autonomous heavy trucks carrying human back-up drivers could be making regular deliveries in five or ten years.

Autonomous trucking could cut down on the primary contributors to truck accidents, factors such as fatigue, boredom, and distractions. There are also significant economic incentives for trucking companies. Unlike human drivers, self-driving trucks can be on the move all day long, helping to complete routes sooner. And tech-optimized speeds and acceleration could improve fuel efficiency.

Daimler, Otto (Uber), and other companies are developing and testing autonomous trucking technology. Autonomous heavy trucks carrying human back-up drivers in the cab could be making regular deliveries in five or ten years.

An Otto-made autonomous truck last year completed a 132-mile beer run in Colorado.

Some Remain Leery of Autonomous Vehicles, New Regulations

Those pushing autonomous vehicles assure the public that a transportation revolution is right around the corner, and that delaying legislation to free up the technology is akin to a utopia roadblock.

The most common argument in favor of self-driving cars is their ability to dramatically reduce traffic fatalities. U.S. road deaths surpassed 40,000 in 2016, the highest level in nearly a decade. The previous two years marked the sharpest two-year increase in traffic deaths in 53 years. According to the NHTSA, human error is to blame for 94 percent of crashes.

“More than 90 percent of these tragedies are linked to human error, driver choices, intoxication, and distraction,” said John Thune (R-SD) at a March 2016 public hearing on self-driving cars before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. “Automated vehicles have the potential to reduce that number dramatically. Unlike human drivers, automated vehicles don’t get tired, drunk, or distracted.”

Mr. Thune and fellow senator Gary Peters (D-MI) formed the Senate Smart Transportation Caucus, which focuses on transportation technology solutions aimed at improving safety and efficiency. They introduced the Senate version of the autonomous vehicle legislation.

In a statement announcing the bill, Mr. Peters said, “Self-driving vehicles will completely revolutionize the way we get around in the future. Our government can help save lives, improve mobility for all Americans… and create new jobs by making us leaders in this important technology.”

The senators’ talking points are nearly identical to those advanced by self-driving car makers.

He and Mr. Thune have also touted the ability of self-driving cars to reduce traffic congestion, fuel use and emissions, and to meet future infrastructure, environmental, and economic challenges.

The senators’ talking points are nearly identical to those advanced by autonomous vehicle manufacturers like Ford, Lyft, Uber, Volvo, and Waymo (Google). This is not a coincidence.

(Click below for page 2.)

These companies joined forces in April 2016 to establish the lobbying group Self-Driving Coalition for Safer Streets. The group’s founding message describes the great potential of self-driving cars to “enhance public safety and mobility, reduce traffic congestion, improve environmental quality, and advance transportation efficiency.”

But the enthusiasm to get more self-driving cars on the road faster is not unanimous. Safety groups and consumers have expressed reservations about autonomous vehicles and the pace at which they are being adopted.

Opponents of the House and Senate legislation argue that autonomous vehicles are being rushed to market in too great a number and with too few regulations.

“The American public will be the crash-test dummies for self-driving cars if automakers aren’t held to higher standards.”

Consumers Union, the policy wing of Consumers Report, wrote a letter to Congress in response to the passage of the House bill, saying, “We are very concerned about provisions in the bill that would change federal law in ways that would open regulatory gaps and fail to adequately protect consumers from vehicle safety hazards.”

For example, some say the exemptions as written could allow manufacturers to have weaker standards for steering systems, brakes, and airbags.

Consumers Union calls for stronger safety protections, far fewer safety exemptions, NHTSA access to crash data for all automated vehicles (not just exempted vehicles), and increased federal funding for autonomous vehicle oversight.

Joan Claybrook, a chairwoman of Advocates for Highway & Auto Safety and the former president of Public Citizen and the NHTSA, said, “The American public will be the crash-test dummies for self-driving cars if automakers aren’t held to higher standards.”

Consumer and safety groups are not merely naysayers of self-driving technology. They agree that the vehicles can have a positive impact, but worry about a half-baked rollout damaging public perception.

“Even a small number of tragedies could negatively influence the public support needed to bring the best of this technology forward,” said Jack Gillis, director of the Consumer Federation of America. Mr. Gillis and other advocates have called for the formation of a specialized autonomous vehicle department employing experts to oversee driverless vehicle standards.

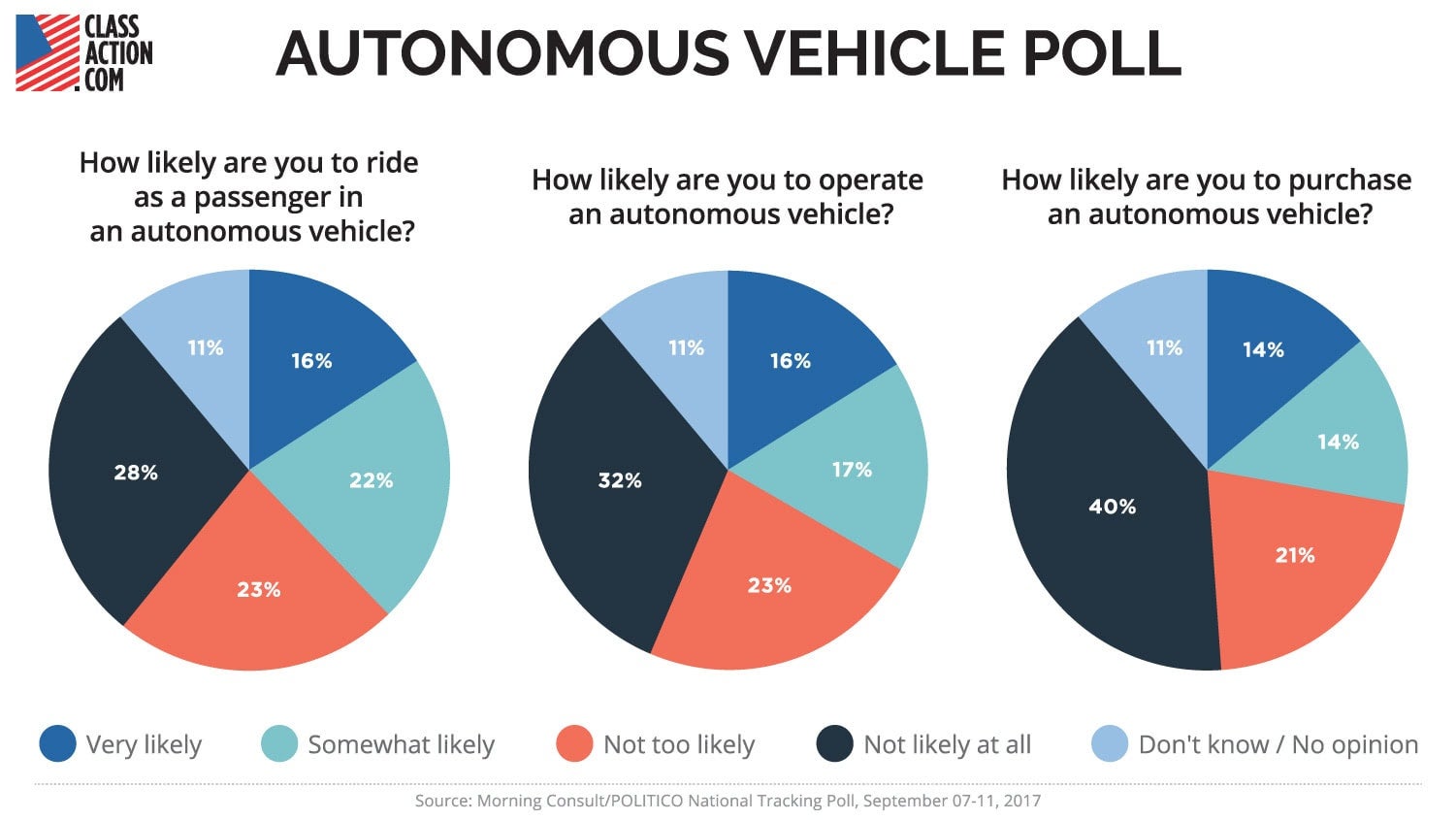

Fifty-one percent said they were not likely to ride in an autonomous vehicle.

Last month the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) concluded “operational limitations” in a Tesla Autopilot system “played a major role” in a fatal May 2016 crash. More incidents like this could undermine Americans’ support of autonomous vehicles, which already is lukewarm.

According to a Morning Consult/POLITICO poll, 35 percent of respondents said automated technology is less safe than human-driven vehicles. Twenty-two percent said self-driving cars are safer than human drivers, and 26 percent were uncertain or had no opinion.

Fifty-one percent said they were not likely to ride in an autonomous vehicle.

Former Auto Regulator Now Lobbying for Private Sector

It’s not a coincidence that members of Congress are repeating industry talking points on autonomous vehicles and pushing forward industry-friendly legislation. The major driverless vehicle players are pouring millions of dollars into lobbying lawmakers.

Cozy relationships between public and private interests are hardly a secret. But the Self-Driving Coalition for Safer Streets presents a stunning conflict-of-interest.

David Strickland will be working to influence the same government group he formerly ran.

The lead counsel and spokesperson for the coalition is David Strickland, the former head of the NHTSA. Mr. Strickland is also employed as a lobbyist at Venable LLP.

The coalition hired Mr. Venable to lobby on its behalf to the NHTSA. OpenSecrets.org shows that Mr. Venable met with the NHTSA twice in 2017 at a cost of $160,000. Acting as lobbyists were none other than David Strickland and Chan D. Lieu, who previously served as Director of Government Affairs, Policy, and Strategic Planning at NHTSA. Mr. Strickland and Mr. Lieu each spent eight years on the staff of the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation.

Mr. Strickland working to influence the same government group he formerly led raises questions about whether public safety will take a backseat to the interests of autonomous vehicle makers.

In September the NHTSA released updated guidelines for self-driving cars. The new guidelines trim the 15-point safety assessment released last year under President Obama down to 12 points. But the bigger story is that the guidelines are now entirely voluntary.

While the assessments are “encouraged,” they’re “not subject to Federal approval.” This means Ford, Google, Uber, and other companies do not have to submit to safety checks or turn over crash data to the federal government for review.

Deborah A.P. Hersman, President and CEO of the National Safety Council, notes that the NHTSA “has yet to receive any Safety Assessments, even though vehicles are being tested in many states.”

Nevertheless, Secretary of Transportation Elaine Chao--who is married to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell--says that “safety is primary” in the revised guidelines.

Mandating safety measures such as clear disclosure, validation processes prior to vehicle deployment, and data sharing requirements will now fall to Congress, says Ms. Hersman.

But the House and Senate bills do little to assuage critics’ concerns on these points. As the heavily lobbied self-driving car legislation is quickly pushed through, skeptics can be forgiven for feeling like carmakers have been handed the keys.